Thanks for reading! If this makes you think, please do share the good word with your friends and colleagues or follow me on Twitter (I have changed my handle to @SashaKaletsky).

In 2004, when I was twelve, the key topics of conversation among my friends included: who would win in a fight between a wolf and a puma; best pizza topping; and policy agenda as world emperor. But another subject was starting to gain mindshare: internet videos.

Perhaps the most popular from that year – and my personal favourite – was “Numa Numa”. If you are over the age of 25, the chances are you have seen this video.

Numa Numa (originally posted to newgrounds.com in 2004, now on YouTube)

The video was viewed tens of millions of times within months of being uploaded (ultimately reaching hundreds of millions of views). It was one of the biggest memes of its year, starting a wildfire of Numa Numa impersonators, impressionists and alternative lip-syncers.

But the creator Gary Brolsma never uploaded another successful video, and eventually disappeared. He currently has a YouTube channel with only 29,000 followers.

The creator broke the internet and nobody asked his name.

Starting with videos like “Numa Numa” in the early 2000s, we’ll cover a brief social internet history, as follows:

2000-05: The internet Wild West. Content is everywhere, and the lack of structure means creators can’t retain their audiences.

2005-20: Creators run this town. Platforms allow users to “follow” creators, who can develop loyal audiences.

2020-?: Return to the Wild West. Platforms deprioritise “followership”, and instead let content compete to win a place in the feed.

And if you don’t care about the history of social media, you can just click the YouTube links and reminisce about the acid trip content people used to watch on the internet.

2000-05: The internet Wild West

In the first half of the 2000s, content was flying around across different platforms. It didn’t matter to me or my friends which platform was hosting our new favourite video, we could share the link just the same in any case. And even within a given platform there was no reason, or even mechanism, for somebody who enjoyed a creator’s content to follow or find their next videos.

This meant that creators who uploaded popular videos did not have an “audience” or “fans”, their videos simply had viewers.

In other words, the vector of distribution was the content, not the platform or the creator.

Pretty much all my favourite videos of the time (I know...) rapidly faded into obscurity:

We Like The Moon, (originally posted to rathergood.com in 2003, now on YouTube).

Badger badger badger mushroom (originally posted to weebls-stuff in 2003, now on YouTube)

Fuzzy Llama (originally posted to albinoblacksheep.com in 2004, now on YouTube)

Side-note: Whether you find these videos funny will be wholly determined by your exact year of birth (i.e. your meme-vintage).

Using the terminology of my previous article, the sites on which these videos were hosted were all “content platforms”. Viewers didn’t care where or whom a video came from; they just wanted to be entertained.

Videos on the internet were like the Wild West; when a new cowboy rolled into town, nobody asked who he was back home; what mattered was what he brought to the table.

2005-2020: Creators run this town

Then in February 2005, everything changed.

Steve Chen, Chad Hurley, and Jawed Karim were underbosses in the PayPal mafia who made a small fortune after eBay’s acquisition of the company in 2002, and were quickly onto the next thing. This time, they wanted to be the dons.

They decided to found a video-sharing site, which they called "YouTube".

Video streaming seemed like a crowded market at the time. But YouTube would be different. Rather than focusing purely on the content, like its competitors, YouTube positioned itself as more focused on the creator of the video. The first ever YouTube video (from April 2005), uploaded by cofounder Jawed Karim, tells you everything you need to know:

This wasn’t supposed to be a viral video (watch it and you’ll see why). The idea was to make it easy to upload content of yourself. Central to YouTube’s vision was the creation of a “profile”, where all the videos users had uploaded were categorised in one place. These videos could then be redistributed to users who’d enjoyed similar videos.

Charlie Bit My Finger, for example, was a 2007 video showing an interaction between two adorable British children.

Like many other videos of its time, it went viral, and racked up tens of millions of views. But the difference with prior viral hits was that it had been uploaded to YouTube. This allowed its viewers to check out Charlie’s family’s profile, who kept posting more content, which also racked up millions of views. 15 years later, and Charlie’s family have made millions of dollars from remixes, merch, and even auctioning the original video as an NFT for $761k (in 2021, you guessed it). Their “fifteen minutes of fame” has lasted a lifetime.

The Charlie Bit My Finger story would not have been possible before YouTube. Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and other platforms of the time had similar dynamics. The creators were the product, not just their content.

This shift in focus from content to creators from YouTube and other platforms resulted in an enormous lengthening of the longevity of creators’ fame. Early creators and influencers saw tremendous and long-term success, which many of them are still enjoying today even if they no longer upload (my partner at Creator Ventures, and cousin, Caspar Lee has turned his 2010 YouTube channel into several successful businesses, even after he “grew out” of his core audience’s demographic).

Consumers followed creators, who gave them content, who in turn continued to watch and tell their friends. It was a beautiful viral loop.

This felt like the End of History. Community-based feedback loops seemed impossible to unseat and creator longevity appeared to be extended forever in the new "creator economy". Creators were running the town.

2020+: Back to the Wild West

But it was not that simple.

In the late 2010s, we saw the entrance of a platform which played by different rules, and put a spanner in the narrative of Fifteen Minutes factor extension: TikTok.

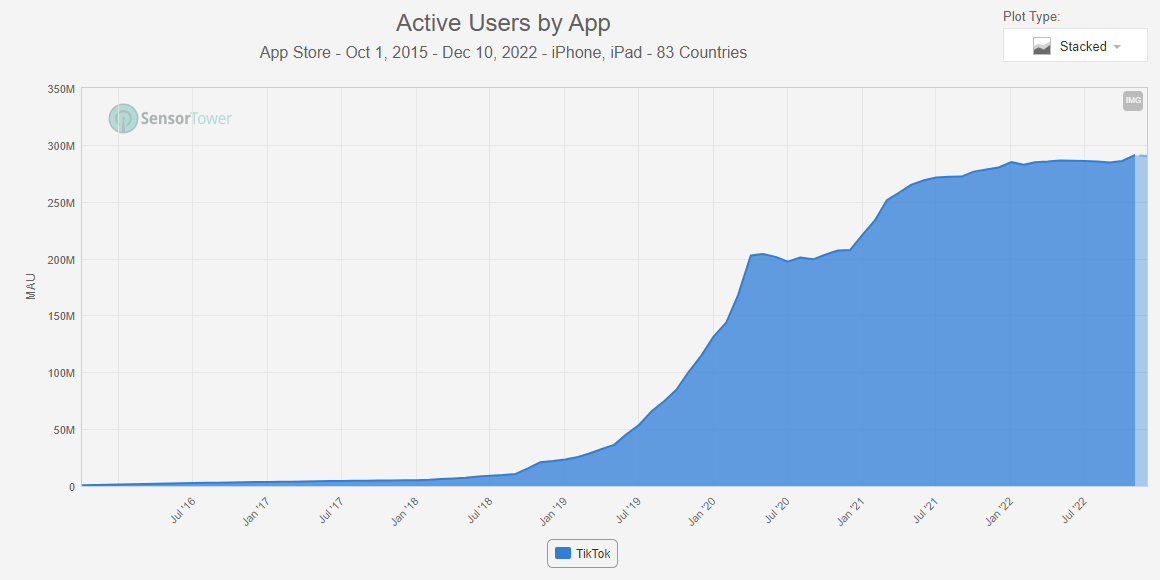

TikTok MAUs since launch (iOS + Android, incl. Musical.ly, excl. Douyin – Source: SensorTower)

TikTok has all the superficial qualities of a follower platform like YouTube: creator profiles, likes, shares, and follows. But TikTok is fundamentally different. It has, as I put it in a prior article, unbundled “entertainment” from “social”.

Instagram Reels, YouTube Shorts, and increasingly even Twitter and LinkedIn are following TikTok’s lead, and becoming more like content platforms (i.e. surfacing content from outside users’ follower graphs).

This ensures that high-quality content maximises reach, but sacrifices the intimacy of the relationship between a creator and their audience.

This has strong negative implications for creators. As I wrote this summer in “The Death of the Creator”, creators on TikTok, Shorts and Reels have less retentive audiences and far shorter lifespans than previous generations. Videos from unknown creators can get tens of millions of views, but if they don’t keep making good content, they will fade as quickly as they rose.

In other words, the social internet is returning to its content-first roots, and a new Wild West.

Content stands alone. If it’s engaging, the platforms – like the Wild West cowboys from our early internet – don’t care too much about where it came from.

The social internet cycle

It can be tempting to view internet history as a steady march towards centralisation, increased connectedness, and deeper “socialisation”. But this is not how it has turned out.

The internet is an unstable system, constantly vacillating between centralised and decentralised, connected and lonely, as well as constantly creating new lenses through which to understand it.

Although we may currently be in transition from a social-to-antisocial phase, there is one thing we know for sure: this isn’t the End of History.

The showdown between internet cowboys and their platform sheriffs is far from over.